“Hey guys!”— that’s Rick Housden’s signature greeting from behind the bar. Usually dressed in a tropical-print shirt and cap, along with a wide grin, Rick telegraphs his effervescent disposition as the namesake bartender at his joint, Rick’s Bar, located inside Pecan Creek Outfitters (“PCO” to the locals) on the north side of Hamilton’s courthouse square. He christened his watering hole in the spring of 2021, a few months after the doors to PCO swung open to the public. The bar’s first three years were fairly slow before Hunter Creasey, Rick’s son-in-law, and Abby Creasey, Rick’s daughter, started hosting trivia on Thursdays in the late afternoon. Since then, Thursdays are the most bustling day for the bar, attracting not just trivia contestants, but a range of others that pile in for drinking and socializing.1I have a repeating calendar event for every Thursday that says, “Drinks with Rick.” Business on Mondays is a close second. Saturdays tend to attract a motley crowd from traffic passing through on Highway 281. No late carousing at Rick’s, though: the bar has the same hours of the retail space, Monday–Saturday, 10 a.m. –6 p.m., though Rick is happy to oblige those who want to stay a little later, which frequently happens on Thursdays.

The bar blends into the northwest corner of the retail space, which is appointed with beautiful, creaky oak floors, a beaded-wood ceiling, and other period details. The retail collection favors a spangly, glam aesthetic for women but offers a more conservative sportsman’s line for men. The store also offers home goods and personal-care items. A wooden, red canoe mounted on the back wall of the bar holds visual sway, along with de rigueur mounted taxidermy and neon beer signs along the bar’s perimeter. Frank Lanfranco, the previous owner of the building, displays a gallery of his paintings nearby. A couple of signs behind the bar announce essential comportments: “POLITICS FREE ZONE” and “No Working During Drinking Hours.” Rick maintains an exceptional tap of rotating craft beers, so there’s always something new to try. A chalkboard lists ABV and IBU values for beer connoisseurs. For wine drinkers, Rick offers a selection of mostly local wines, but it’s his beer tap that stands out—he’s a beer drinker. Occasionally, some delectable munchies from Wenzel’s deli, located around the corner, get shared among patrons, and then there’s the giant jar of Texas Trash that gets freely distributed. Tipping is a little tricky: unless you’re quicker or slyer than Rick—and that’s hard—you may miss your chance to add a credit card tip. However, there is a tip jar.

Rick knows the regulars by name, and his priority is keeping his patrons happy. He does that with aplomb. No novice, he managed the local country club for a while and bartended there. Rick has an antecedent in Charley Day (1861–1918), a beloved saloon keeper from Hamilton’s distant past. “Charley Day, well known to everybody in this section of Texas as one of the best and most thoroughly honest and reliable saloon men that ever went behind a bar … [He] has been in the liquor business nearly all his life, practically all of which has been spent in and near Hamilton, and it is safe to say that no man in this section has more or truer friends than Charley Day” (“Charley Day Article”).

Social settings, including bars, predictably reflect the various strata and affiliations of its patrons. Rick’s clientele skews senior and usually splits into camps. On trivia day, the early arrivers grab bar seats and divide into teams, while others hover on the sidelines. Couples typically stay together. There is a slightly younger, perhaps cooler, subgroup that has its own corner. Some prefer to hang out in the lounge area. A plethora of discussion topics energize the space. But the bar’s raison d’être is getting people together, enabled by the drink.

Rick’s Bar joins a long history of humankind’s relationship with drinking, particularly drinking in public places where alcohol is served. Humans have enjoyed imbibing ever since discovering fermentation. One of the earliest known references to alcohol occurs in Genesis: “And Noah began to be a husbandman, and he planted a vineyard; And he drank of the wine, and was drunken and he was uncovered within his tent.”2Genesis IX: 20, 21 In America, drinking establishments have existed for well over four hundred years. Most regard social drinking as more attractive than solitary drinking, so public bars naturally evolved (Brown 11). In early America, taverns and their like were “almost the only recreation for the poor,” offering a balm to help them cope with their difficult lives (Brown 9). Discussions that led to the American Revolution were held in taverns across the thirteen colonies (Erdoes 26). States were named, capitals founded, candidates announced, and elections held inside their doors (Erdoes 9).

Many local governments encouraged businessmen to open taverns, and in many towns it was compulsory (Brown 13). Men went to taverns to fraternize with other men, gamble, listen to music, and play games; moreover, they could speak freely and often crudely. And they did not have to wash up (Brown 11). One of the powerful draws for patrons was that these places offered an escape from propriety, which probably still holds true today.

Artists and intellectuals have a long association with saloons and bars: boozing, socializing, and sharing ideas thrived in their atmospheres (Artist Bars and Art History). Which reminds us that the word saloon comes from a misspelling of salon, which means “a periodic gathering, usually at the home of a distinguished woman, of persons of note in artistic, literary, or political circles” (Erdoes 3).

The multifarious saloon, beyond being a drinking place, acted in many capacities: eatery, hotel, bath and comfort station, livery stable, gambling den, dance hall, bordello, barbershop, courtroom, church social club, political center, dueling ground, post office, sports arena, undertaker’s parlor, library, news exchange, theater, employment agency, trading post, and grocery, among many others (Erdoes 9). They were “universal meeting places” (Erdoes 232).

As easterners moved westward, they naturally recreated the institutions they knew in their original homes, including drinking places (Brown 30). Of course, they adapted them for much rougher conditions, and they eventually became known as saloons. Saloons did not replace older monikers, such as taverns, alehouses, or taprooms, until the 1840s (Erdoes 4). Wagon trains were known to set up “tent saloons” or other improvised “thirst quenchers” on their way out West (Brown 24). Most of these early “saloons” were very primitive—usually a tent, dugout, or other structure built out of what was available—but clearly a priority to get up and running. In the frontier American West, saloons were typically the first businesses to start in a town (the town of Hamilton followed that trend), and they often surpassed other enterprises in quantity and profitability (Brown 15). The number of saloons in a town was a barometer of its economic health (Erdoes 37).

A frontiersman typically spent more time in a saloon than he did outside of one (Brown 15). No wonder, considering the buffet of amenities they offered to patrons regardless of social or economic standing, which included male (and sometimes female) companionship, a way to get and discuss news, a place to gamble (cards, pool, or slot machines), music, a free lunch, and of course, lubricating refreshments (Brown 15–17). Charles Russell, the famous western painter, once observed that drinking had a way of revealing a man’s true character: “Whiskey has been blamed for lots it didn’t do. It’s a brave maker. All men know it. If you want to know a man, get him drunk and he’ll tip his hand. If I like a man when I’m sober, I kin hardly keep from kissing him when I’m drunk. This goes both ways. If I don’t like a man when I’m sober, I don’t want him in the same town when I’m drunk” (Erdoes 68). In the frontier days, saloons were for men only, with the exception of “nymphs of the prairie” or outright prostitutes (Erdoes 6, 71).

In a typical, one-street town of the 1870s, every other business was a saloon. Most saloons had false-fronts attached, which made them look like fancier, two-story places; behind was a crude, one-story building (Erdoes 37). At least one back door and several side doors were available for a quick exit in case of an altercation (Brown 18). The ubiquitous swinging front doors—by now almost synonymous with the frontier saloon—were designed with practicality in mind: they hid what was going on inside but at the same time enticed customers; they were also easier to open for a drunk patron (Brown 19). More refined, Victorian-style saloons came later: “The moment when mahogany bars, pianos, gilded mirrors, and white-shirted bartenders appeared depended on location and developments” (Erdoes 36).

Though it is hard to separate the saloon from the frontier ethos, it is important to know that as ubiquitous as they were, they still encountered fierce opposition from temperance supporters and later prohibitionists (Brown 23). And not all frontier denizens frequented or got rowdy at the local saloon—most had “wholesome” family lives. Many western towns banned saloons, and the temperance movement was strong, especially in areas with Mormon presence or in places that had a prevalence of socialist farming communities founded on the principles developed by Horace Greeley3Wikipedia, accessed October 21, 2025: “… Among many other issues, he urged the settlement of the American Old West, which he saw as a land of opportunity for the young and the unemployed. He popularized the slogan ‘Go West, young man, and grow up with the country.’ He endlessly promoted radical reforms such as socialism, vegetarianism, agrarianism, feminism, and temperance …” and Nathan Meeker. Greeley once wrote, “Fully half of the earnings of our working men are fooled away on this abominable witch broth …” (Brown 23). Immigrants, especially Germans and Irish, brought their own drinking traditions, i.e. heavy, to America and were not used to the moral judgments they encountered (Brown 13). Many saloons made themselves more palatable by disguising themselves as grocery stores or hotels (Brown 29).

Saloons formed an important part of Hamilton’s history, even though their fraught reputations in the public’s eye have stymied them from fair reportage. Hamilton’s bar scene started early when Ezekiel Manning, Hamilton County’s first sheriff and one of the organizers of the county in 1858, built the first tavern around 1855 (“Parade of Progress”).4L.V. (Lewis Vincent) Manning (1861–1956), son of Ezekiel Manning, ran the Lone Star Saloon before 1904 (in 1904, L.V. moved to Fort Worth per Steve Manning), which may have been located on East Henry Street (Rat Row). See Postscript. It was made of split logs and was located on southwest corner of the current courthouse square when it was only a thicket of brambles (Hamilton County Texas History; “Parade of Progress”). By 1878, the town had two saloons (“Parade of Progress”). True to historical precedent, churches followed the saloons in Hamilton, starting in 1880 with the Presbyterian Church (“Parade of Progress”). Ironically, early saloons hosted church services (Erdoes 119). Many might also be surprised to find out that the Crescent Saloon served as the Hamilton County Courthouse between 1877 and 1878 (“Hamilton County Courthouses”).

Rick admits that he was not aware that his block of East Henry was once a notorious strip of saloons known as Rat Row. A concentration of watering holes coalesced there, and proper ladies were never seen on that “wicked” stretch (Hamilton County Texas History 14). “The north side of the square had several saloons on it and it took on a pretty bad name … Ladies avoided going over that way, and cautioned their daughters to stay completely away, even if they had to walk completely back around the square” (“Elsie Walton Biography”). In early 1911, a letter republished in The Hamilton Rustler recollects some details about Rat Row: “You remember there was a side of the square in Hamilton called Rat Row. There were six saloons [corrected to five by the respondent] on it” (“Editorial on Rat Row”). Incidentally, the second jail in Hamilton County, built in 1877 by Arthur Northcraft, was conveniently located behind Rat Row (“Parade of Progress”).

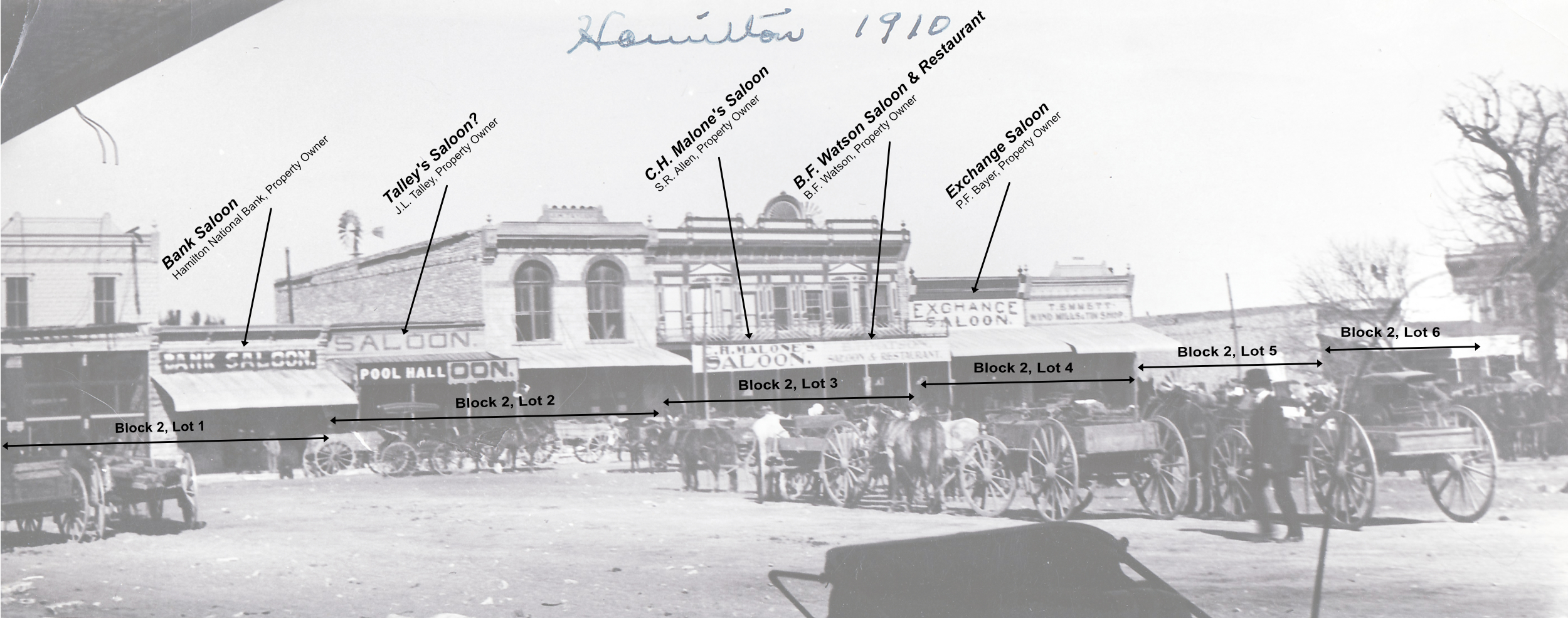

Saloons reached their peak on Rat Row around 1910, maybe a little earlier, when the population of the town was about 1,500 people (“Hamilton’s Historical Growth”). Around 1900, there were three saloons on Rat Row, and one had a hotel above it (probably above Malone’s or B.F. Watson) (“Elder Sees Many Changes”). Around the same time, George Battle ran the Silver Dollar Saloon, which was likely located next door to the west of B.F. Watson (“Silver Dollar Saloon”).

A 1910 photo reveals five saloons up and down Henry Street across from the courthouse, which was about average for a town of Hamilton’s population, though there were likely more around town (Erdoes 82). Bank Saloon, the westernmost business (now 101 East Henry Street, part of the Hamilton County Courthouse Annex), was so named because the property was owned by the Hamilton National Bank. Next door to the east was another saloon—the name is not known—but the property was owned by J. (John) L. Talley (he purchased the property from A. Whitte for $3,000 in 1907). Some old-timers recall a “Talley’s Saloon,” which was an Irish pub, and this may have been the location. The space is now occupied by Ray’s City Drug. Two doors down to the east was Malone’s Saloon (property owned by S.R. Allen, et al.; Allen purchased the space from IOOF Lodge No. 216 in 1907 for $5,150), and next door to the east was B.F. Watson Saloon & Restaurant, owned by B.F. Watson. Lucian Miller was a well-regarded saloon keeper that worked there (“Lucian Miller Article”). PCO, located at 107/108 East Henry Street, now straddles the spaces once held by Malone’s and B.F. Watson, and the lot probably had a hotel and possibly a brothel upstairs. The last pub to the east was Exchange Saloon, owned by P.F. Bayer, likely named in reference to nearby banks and now addressed as 111 East Henry, where Germania Insurance is currently located. The Hamilton Rustler, was once printed in a space above one of the saloons on the north side of the square, probably either Malone’s or B.F. Watson (“General Merchant Spurlin”).

There were other saloons peppered around town doing business at various times. Among them was the Basement Saloon (once located on the northwest side of the square and the first rock building built there), owned by Marion Graves. Hervey Chesley recalls that the bartender of the Basement Saloon, a “Mr. Williams,” had to settle up with Justice of the Peace Squire Lloyd, aka “Square,” every Monday after a rowdy weekend. Mr. Williams negotiated the fines down and paid them, with most of the money going into “Square’s” pocket (“Working”). Bars had to keep a $1,000 bond with the court to ensure the peace was kept (“Working”). Other joints were McGuire’s/Tony’s Saloon, the “Ideal Saloon,” the Crescent Saloon, and Seagle’s (sometimes referred to as “The Baptist Saloon” since it was near the church) (“Mr. William Secrest”). A photograph shows that a location of Malone’s was once near the corner of Bell and Main. Its awning sign reads: “OPEN ALL HOURS.” Luther Price and his brother, Will, were both connected with a saloon on the north side (“Luther Price Article”). Bob Matheson’s Saloon was also located on the north side (“Henry Goode’s Roughhouse”). Hervey Chesley recalls a list of saloon owners around this time: “Pap Reinhert, Bob Matheson, and maybe [Lewis] Manning and Watson were running them” (“John Fowler”; “Mr. William Secrest”). King and Fortran once owned a saloon in the building where John Mark ran a store (“Chain Saloon Princes”). O.O. Miller kept a saloon on the east side where the Main & Chesley law office was later located (“Double O. Miller”).

There were also watering holes further afield, revealed in an advertisement published in June 1911: “Summer time beverages, and fine old whiskey for medicinal purposes at McPigs Saloon, at Aleman. Stop in when passing this way” (“McPiggs Saloon Aleman”). J. (John) L. Talley likely closed his “Irish” saloon in 1912 and set up a saloon in Temple known as The Cozy Corner Bar, where he provided mail-order service, actively soliciting customers in Hamilton (“John L. Talley Article”). Other mail-order outfits also serviced the Hamilton area, such as The Mirror Ball in Waco (“Mirror Ball Article”) and J.A. Bennett’s Crystal Saloon, out of Fort Worth. The Mirror Ball and J.A. Bennett both advertised in the local paper.

No issue seemed to roil the Hamilton area more than the prohibition and related temperance movements. The Anti-Saloon League, a prominent temperance organization, was certainly active in Hamilton (“Temperance Movement”). Saloons have long been the target of proper society, though of course there was a good bit of hypocrisy in the mix. There has always been an “uneasy tolerance toward public drinking places” (Brown 21). In 1938, local pioneer R.A. Smith wrote, “At an early date in our territory our young people, directed by some older heads, were organized into a temperance order, known as the United Friends of Temperance. Here all members took a binding obligation never to take any intoxicants as a beverage. Their motto was ‘Touch not, taste not, handle not.’ The influence is felt in our community today, and this accounts for the ‘dry’ sentiment found here …” (“Parade of Progress”). Sometime in the 1880s, the town of Hamilton went “dry,” but the alcohol business furtively continued: Dr. Perry’s drugstore sold “prescription” whiskey at a vigorous pace, and some saloons likely kept operating under the radar (“Christmas Time”). A later vote on January 26, 1909, turned the town “dry” again, and the saloons on Rat Row rapidly declined. A newspaper article from 1911 reports that all the bars along that stretch were empty and available for discounted rents (“Editorial on Rat Row”). “The efforts of all these groups coalesced in voting out saloons and electing officials who would deal effectively with the criminal element. The liquor problem was one which refused solution. Where saloon keepers had formerly profiteered, these profits now went to doctors who wrote prescriptions for whiskey and the druggists who still could sell it legally. The moonshiner and bootlegger eventually became important in the business” (“Chesley Interviews Introduction”). That same year, in 1911, Haskell Harelik started renting 107/108 East Henry Street, previously two saloons, and opened his dry goods store there that stayed in business until 1989 (“Dorothy”; “Haskell Harelik Dry Goods Co.”).

Prohibition reached a national level with the U.S. adoption of the Eighteenth Amendment, ratified in January 1919, enforced starting in 1920, and removed in 1933 (“Prohibition Elections Texas”). That said, it would not be until 1935 before Texas repealed its 1919 statewide prohibition (“Prohibition Elections Texas”). The City of Hamilton has flipped numerous times over the years, but it last voted to become “wet” on November 8, 2011 (395 for; 269 against) (Yates).

And so the tap ebbs and flows. Rick’s Bar may be the catalyst for a revival of bars on old Rat Row, and it would seem that the community would be amenable to “having another round.” Rick and his customers now share company with the ghosts of saloons past. His bar joins a long history of saloon businesses in Hamilton and beyond—essential institutions that, despite their vacillating reputations, perform the vital task of helping connect people. A 2025 advertising campaign from Heineken—in reaction to artificial intelligence-based companions—reminds us of a long-known truth: “The best way to make a friend is over a beer” (“Heineken Rejects AI Companionship”).

With thanks to Jim Eidson, Chair, Hamilton County Historical Commission; Rachel Geeslin, Clerk, Hamilton County; Rick Housden; Stacey Moore, Genealogy Supervisor, Hamilton Public Library; Coni Guinn, Director, Hamilton County Historical Museum; John Ratliff, GIS Dept/Deeds/ARB Liaison, Hamilton Central Appraisal District; and James Yates, Judge, Hamilton County

Postscript

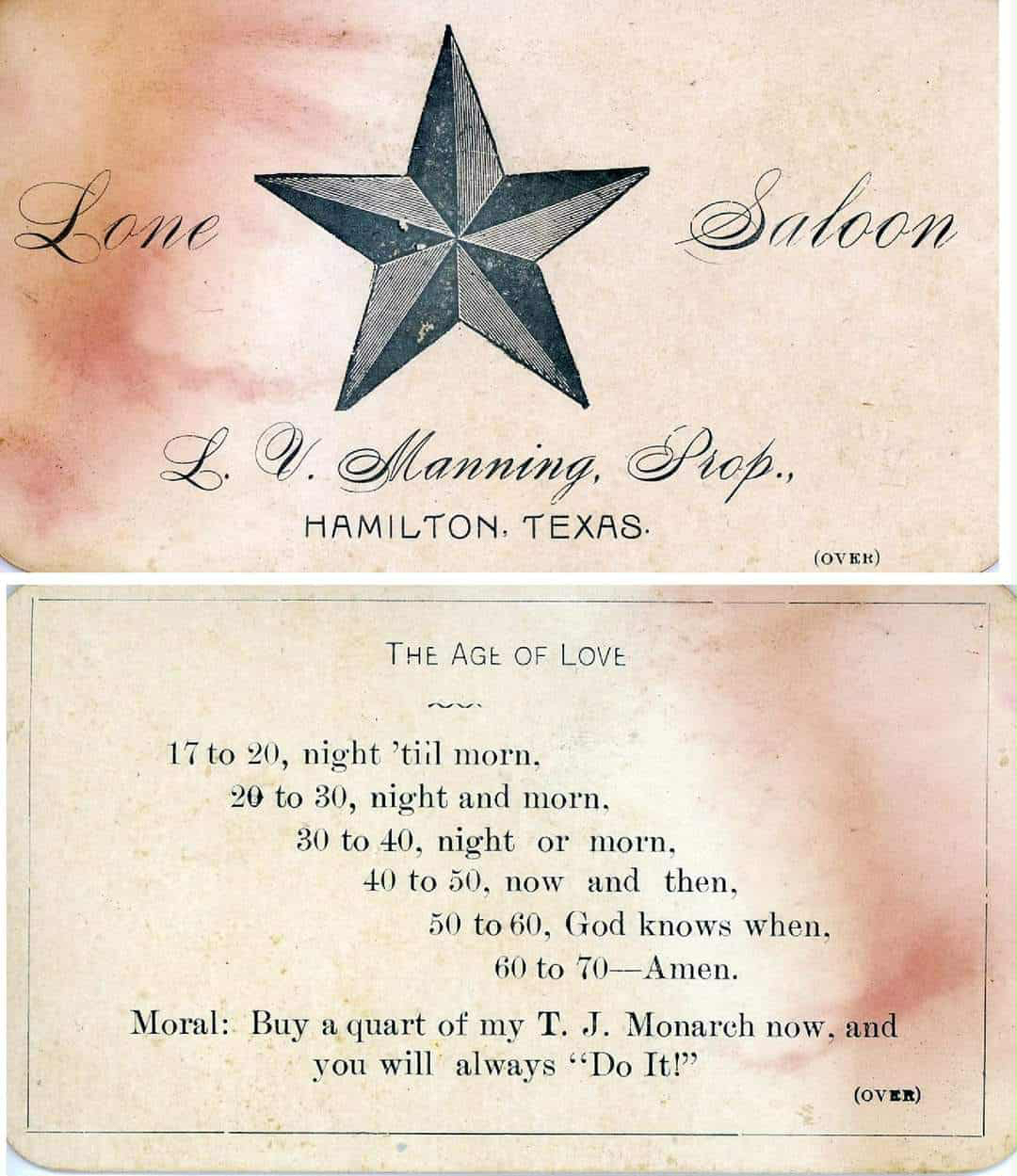

L.V. (Lewis Vincent) Manning (1861–1956), son of Ezekiel Manning, ran the Lone Star Saloon before 1904 (in 1904, L.V. moved to Fort Worth per Steve Manning), which may have been located on East Henry Street (Rat Row).

Works Cited

A History of Hamilton County Texas. Hamilton County Historical Commission, 1979.

“[Article about McPiggs Saloon in Aleman].” The Hamilton Rustler, 5 June 1911.

“[Article on Lucian Miller].” The Hamilton Rustler, 21 Sept. 1911.

“[Article on Luther Price].” The Hamilton Rustler, 28 Dec. 1911.

“At Christmas Time.” People and Places: Gazetteer of Hamilton County, TX, https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~gazetteer2000/genealogy/chesley/ches_188.htm. Accessed 26 Oct. 2025.

Brown, Robert L. Saloons of the American West: An Illustrated Chronicle. Sundance Books, 1978.

“[Charley Day Article].” The Hamilton Rustler, 9 Feb. 1911.

“Dorothy Harelik.” The Hamilton Herald-News, https://www.thehamiltonherald-news.com/Content/Dorothy-Harelik. Accessed 26 Oct. 2025.

“Double O. Miller.” People and Places: Gazetteer of Hamilton County, TX, https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~gazetteer2000/genealogy/chesley/ches_198.htm. Accessed 26 Oct. 2025.

“[Editorial on Rat Row].” The Hamilton Rustler, 11 Mar. 1911.

“Elder S. A. Rains Sees Many Changes.” People and Places: Gazetteer of Hamilton County, TX, https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~gazetteer2000/genealogy/news1934/rains_sa.htm. Accessed 26 Oct. 2025.

“Elsie (Bledsoe) Walton.” People and Places: Gazetteer of Hamilton County, TX, https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~gazetteer2000/genealogy/across/walton_e.htm. Accessed 26 Oct. 2025.

Erdoes, Richard. Saloons of the Old West. Gramercy Books, 1997.

“Hamilton County Courthouses.” People and Places: Gazetteer of Hamilton County, TX, https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~gazetteer2000/genealogy/hamil_co/courthou.htm. Accessed 26 Oct. 2025.

“Hamilton, Texas: History, Growth, and Community.” Handbook of Texas, Texas State Historical Association, 1952, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/hamilton-tx-hamilton-county.

“Haskell Harelik Dry Goods, Co.: Our Windows Tell You of Fashion’s Latest Decrees, Forward With Hamilton Since 1911.” People and Places: Gazetteer of Hamilton County, TX, https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~gazetteer2000/genealogy/pioneer/harelik1.htm. Accessed 26 Oct. 2025.

“Heineken USA Rejects AI Companionship after Friend’s Ads Are Defaced.” Ad Age, https://adage.com/creativity/work/aa-heineken-usa-best-way-to-make-a-friend/. Accessed 24 Oct. 2025.

“Henry Goode Raises Roughhouse.” People and Places: Gazetteer of Hamilton County, TX, https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~gazetteer2000/genealogy/chesley/ches_074.htm. Accessed 26 Oct. 2025.

“[Introduction to Chesley Interviews].” People and Places: Gazetteer of Hamilton County, TX, https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~gazetteer2000/genealogy/chesley/introduc.htm. Accessed 26 Oct. 2025.

“John Fowler.” People and Places: Gazetteer of Hamilton County, TX, https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~gazetteer2000/genealogy/chesley/ches_175.htm. Accessed 26 Oct. 2025.

“John L. Spurlin, the General Merchant.” People and Places: Gazetteer of Hamilton County, TX, https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~gazetteer2000/genealogy/chesley/ches_037.htm. Accessed 26 Oct. 2025.

“[John L. Talley Article].” The Hamilton Record and Rustler, 18 Jan. 1912.

“King and Fortran – Princes of Chain Saloons.” People and Places: Gazetteer of Hamilton County, TX, https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~gazetteer2000/genealogy/chesley/ches_173.htm. Accessed 26 Oct. 2025.

“[Mirror Ball Article].” The Hamilton Herald and Rustler, 11 July 1912.

“Mr. William Secrest.” People and Places: Gazetteer of Hamilton County, TX, https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~gazetteer2000/genealogy/chesley/ches_176.htm. Accessed 26 Oct. 2025.

“Parade of Progress: Hamilton County, 1858-1958.” Hamilton Herald-News, 1958.

Pool, Oran Jo. A History of Hamilton County. The University of Texas, 1954.

“Prohibition Elections in Texas.” Texas Almanac, https://www.texasalmanac.com/articles/prohibition-elections-in-texas. Accessed 24 Oct. 2025.

“Temperance Worker Coming.” The Hamilton Herald and Rustler, 16 Apr. 1914.

“The Legendary Bars Where Famous Artists Drank, Debated, and Made Art History.” Artsy, https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-legendary-bars-famous-artists-drank-debated-made-art-history. Accessed 24 Oct. 2025.

“The Silver Dollar Saloon.” People and Places: Gazetteer of Hamilton County, TX, https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~gazetteer2000/genealogy/chesley/ches_177.htm. Accessed 26 Oct. 2025.

“Working in the Old Basement Saloon. Mr. Henry Goode et al.” People and Places: Gazetteer of Hamilton County, TX, https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~gazetteer2000/genealogy/chesley/ches_077.htm. Accessed 26 Oct. 2025.

Yates, James. [Results of November 8, 2011, Local Option Election]. 27 Oct. 2025.

- 1I have a repeating calendar event for every Thursday that says, “Drinks with Rick.”

- 2Genesis IX: 20, 21

- 3Wikipedia, accessed October 21, 2025: “… Among many other issues, he urged the settlement of the American Old West, which he saw as a land of opportunity for the young and the unemployed. He popularized the slogan ‘Go West, young man, and grow up with the country.’ He endlessly promoted radical reforms such as socialism, vegetarianism, agrarianism, feminism, and temperance …”

- 4L.V. (Lewis Vincent) Manning (1861–1956), son of Ezekiel Manning, ran the Lone Star Saloon before 1904 (in 1904, L.V. moved to Fort Worth per Steve Manning), which may have been located on East Henry Street (Rat Row). See Postscript.